Setting the Stage: Towards Equal Entrepreneurship

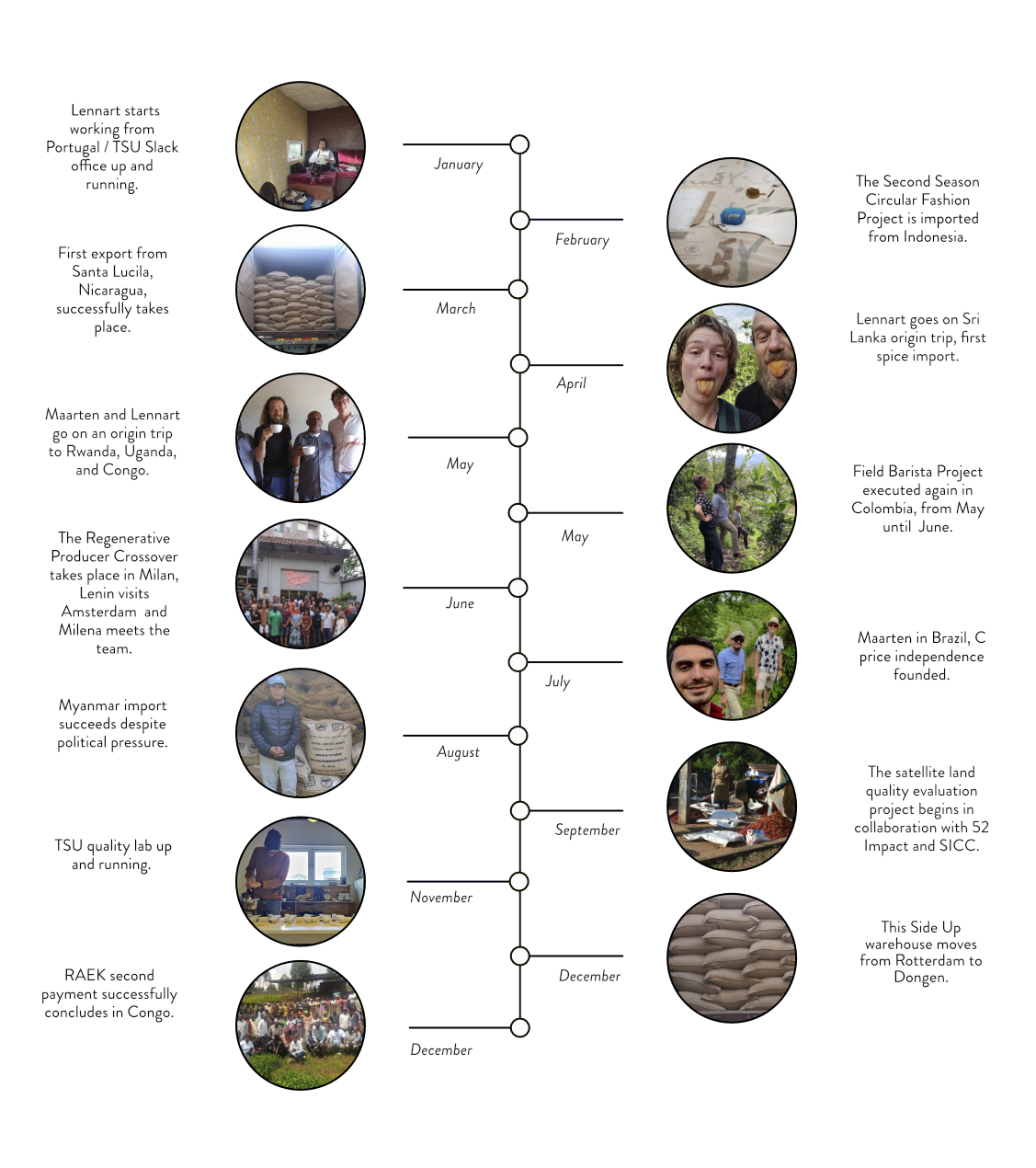

When I set out for Indonesia, I had one clear objective: to sit together with our partners and figure out a way to work sustainably for the next decade. We’ve been working with Ontosoroh for many years, and been a steadily growing client for them and all the farmer communities as well. Starting out with 600 kilograms in 2017 from Pak Lodovikus from Asnikom in Flores, we’re now looking at more than 4 full containers, from partners from Java, Flores, Sulawesi and trials from Papua as well. Much of the coffee goes into “everyday blends” at offices, hospitals, hotel lobbies and small cafes: it’s the robusta component that gives that extra kick so many consumers are looking for. It’s in high demand, but comes at a price cap. But it can offer big volumes, long contract times, with steady return sales. It is the kind of coffee that can give stability to both farmer and roaster.

On the other hand, the internal Indonesian specialty coffee scene is on the rise, and that gives some funky arabica fruitbombs, and unique experimental processes as well. Indonesia is one country in our portfolio, but it’s one with many faces, realities and above all: many, many flavors. Here the topics are about sublime control of all the processing steps, to create that award winning cup that can make farmers proud, and inspire the generation to come, because coffee is a cool product. And perhaps, one day, your picture will be hanging in that fancy café in Paris or Berlin.

Maarten, Kerissa, Giancarlo, Dennis, and Steven with ASNIKOM members after a workshop on developing long-term partnerships for sustainable coffee trade during the origin trip

To the background of this, the global coffee market has been in flux, and in times of uncertainty, we have two choices—we can stare at numbers on a screen or look each other in the eyes and ask, what’s really happening on the ground? How do we take this new reality and navigate it as partners in a value chain that has proven its resilience time and time again? How do we prepare and commit to the future, together?

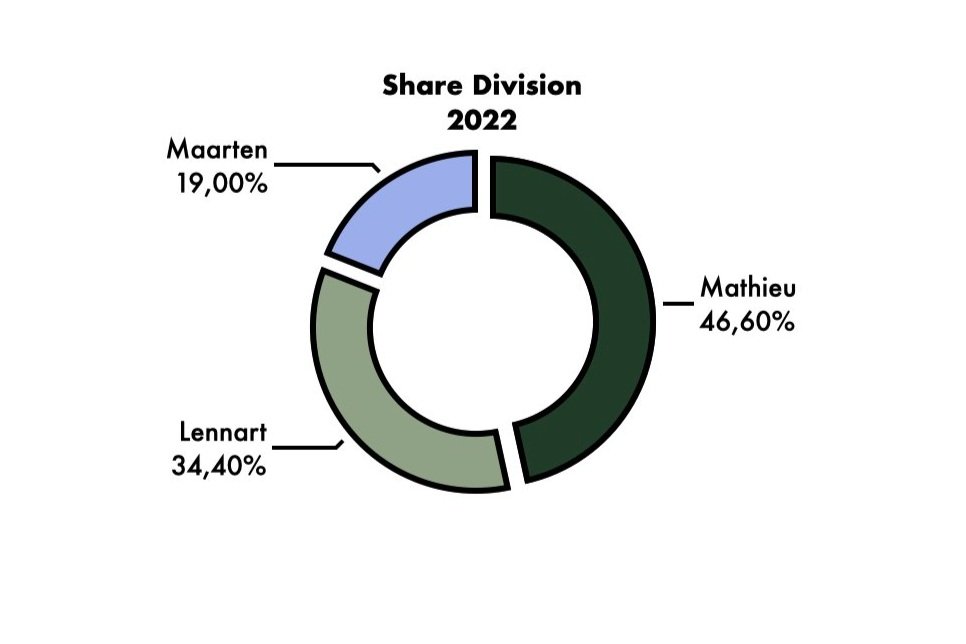

I wasn’t alone on this journey. I traveled with Kerissa from Wakuli, Giancarlo from Special Roast, Dennis from Koepoort, and Steven from Eight. Our collective goal was to explore what’s possible on both ends of the supply chain to ensure the continuity of our partnerships. The reality is often less daunting and far more human than one might expect. As a value chain, we hold our place because we add value—because what we do is worth paying for. When both sides approach the conversation as equal entrepreneurs, open about their realities, the response is empathy. A farmer doesn’t want a roaster to go bust, and a roaster doesn’t want a farmer to struggle. It really can be that simple.

Exploring the Realities on the Ground

Our first stop was Flores, where we met with our partners at Asnikom to discuss robusta production. Decreasing yields, aging plants, and the urgent need for rejuvenation were central themes. But the conversation wasn’t just about agronomy and technical fixes; it was also about culture. Some farmers shared their deep respect for their coffee plants, passed down from previous generations. Uprooting them wasn’t just a financial decision—it was a deeply personal one. Here, we were open about what the producers needed to have an income that would make them happy, and the roasters communicated what their budget was - and why. They showed videos, photos and packaging of where the coffee ends up, and what opportunities and limitations this provided. We got to ballpark financial figures, after hours of drawing on a whiteboard and opening all the books.

On Java, we found a very different reality with the Kojoyo cooperative, which represents the Candiroto and Sindoro coffee regions. Here, young farmers are bringing fresh energy to coffee production, engaging in fermentation experiments and planting new varieties. The challenge was maintaining their momentum and ensuring they stay connected to European roasters. Strengthening these direct links would “feed the pride” of these young producers and keep their enthusiasm for high-quality coffee growing. Could this community also be an inspiration for other “aging coffee regions”? We asked about the reason for the success. Cahyo, the 32 year old robusta farmer, shared with a huge smile that he’s been making more than four times the minimum income last season: “and that with coffee!”. It was nice - and refreshing - to see the young farmers gathering together at their packing facility. Not to do anything - cause it was off season - but to be together, as friends, as a community. Drink a nice coffee, roast it, talk to the clients from far away. It was a relaxed though professional setting.

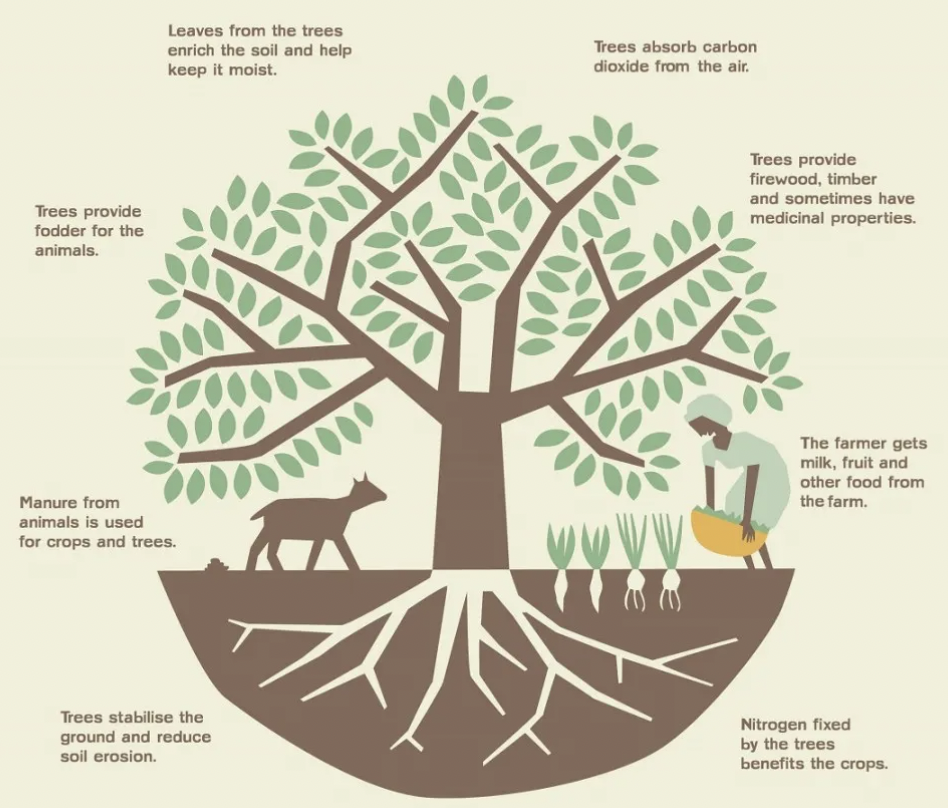

In southern Sulawesi, we visited our partners in Gowa Malino, where we discussed their participation in the Cup of Excellence and strategies for consistently producing high-quality lots. A new generation of coffee growers is emerging here as well, and it was exciting to cup their latest trials. Further north, in the mountainous regions of Sesean and Buntu Ledo, we faced a more troubling reality. Just a few years ago, their coffee scored 88 points; this season, it dropped to 78. The culprit? Climate change. Shifting rainfall patterns disrupted drying processes, leading to taste defects and crop struggles. Together with Adri from Ontosoroh, we started planning an entirely new drying facility—raised drying beds, a solid roof, proper ventilation. By the end of the year, unexpected weather shifts won’t catch them off guard again.

Visiting Onsotoroh’s operations and meeting the incredible community behind the process—from post-harvest work to creating sustainable bag inks with leftover coffee. These are the people who help bring this coffee to life

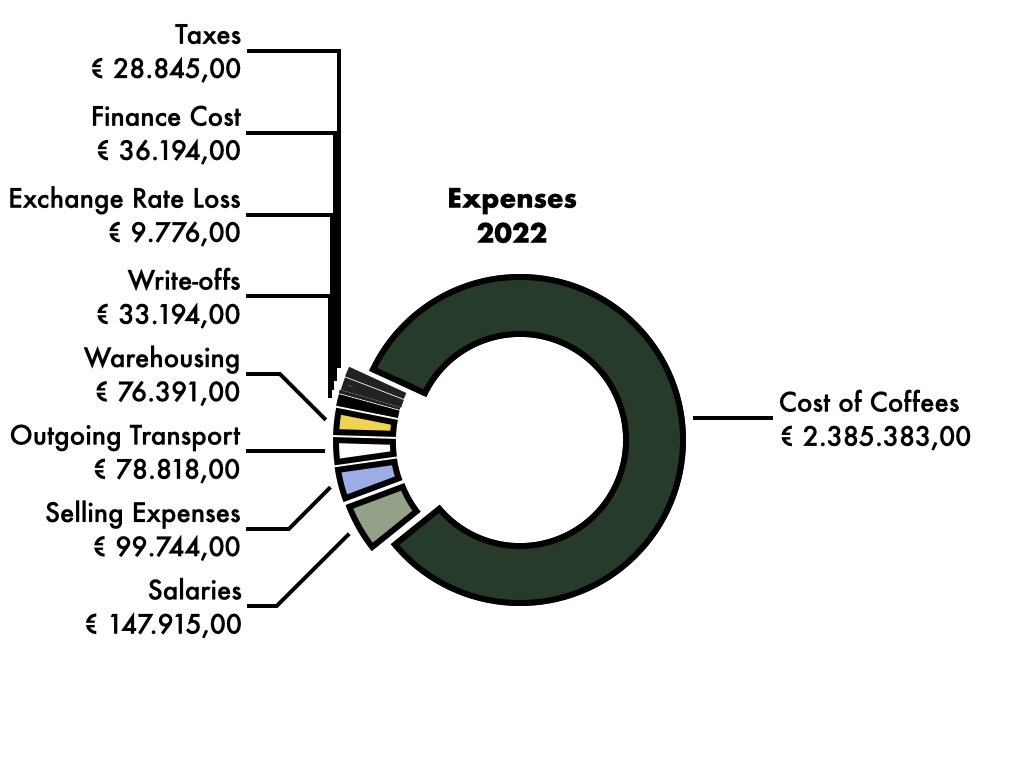

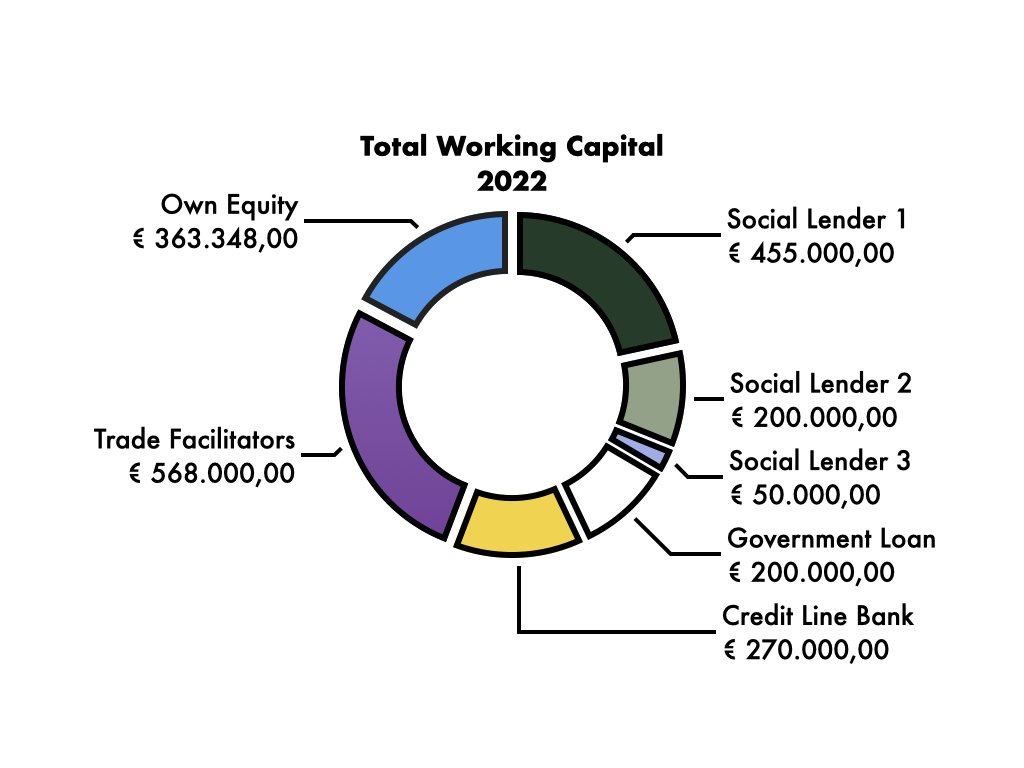

The Common Thread: Anticipation

Despite the diverse challenges in each region—whether agronomy, climate change, generational shifts, or market access—one issue kept resurfacing: prefinancing. If farmers struggle to cover basic costs like harvesting and labor, all the momentum we build together collapses. Many times, prefinancing means paying in advance—often covering 50% of the crop’s value—so farmers can invest in their harvest and pay their pickers. This Side Up has long collaborated with organizations like Progreso and Rabo Foundation to facilitate these financial structures, but perhaps more needs to be done. More options, more opportunities.

After all, in a value chain built on strong relationships, coffee is often sold before it even leaves the tree. It’s prebooked during its growing cycle with the expectation that quality will meet expectations. The real question is, how do we tighten these connections even further? How do we ensure producers can confidently grow what’s ordered, backed by financial security?

This is the puzzle we’re determined to solve in the coming months. Stabilizing a turbulent market requires commitment—and skin in the game—from both sides. Coffee remains a complex product, but by standing close, being transparent about what’s possible and what’s not, we can go much further together.